Brief introduction to the history of performance

Performance draws its origins from the events organized by the avant-gardes of the 20th century such as the Futurists, the artists of the Bauhaus (Germany) or the Dadaists of the Cabaret Voltaire (Zurich).

They performed poetic actions. Already at that time the performance is recognized as a subversive art, setting itself apart from the strict rules of the arts of the time (painting and classical sculpture, theater…).

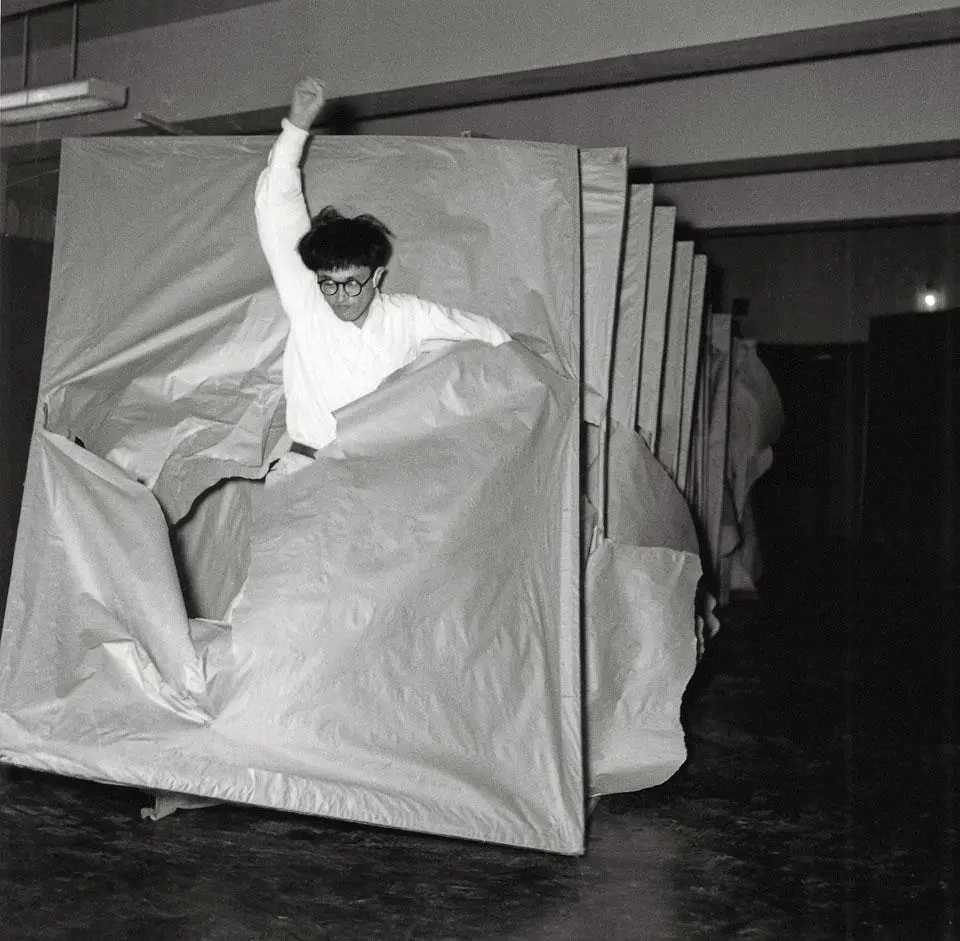

It established itself as an autonomous artistic genre in the early 1960s in Europe, the United States and Japan, supported by movements such as Fluxus, the happenings of Kaprow, Viennese actionism or the performances of Gutaï. Performance is often used during popular protests or demands. He wants to be provocative and denigrate all affiliations with the art market.

It is an art that is characterized by its relationship to time, its interaction with the public and its archiving.

Eric Mangion explains that originally the term «performance» appeared in the 1970s. It comes from the term performing which refers to the accomplishment of a gesture or an action in the live performance. In the etymological sense, it evokes ‘what takes shape’ or tends ‘towards form’, which refers to an intermediate state.

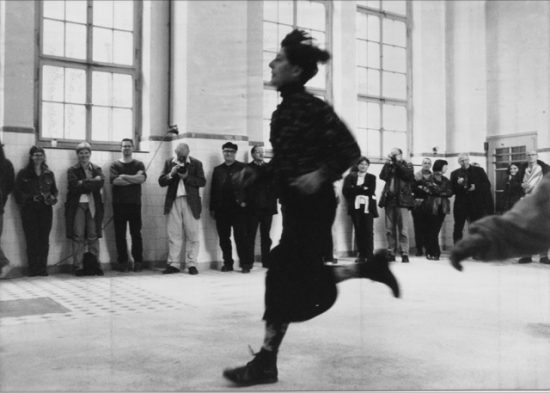

These practices are based on three main elements: the body, space, and time. They are actions, events, happenings, etc. organized by an artist who uses his own body or calls upon other people.

The boundaries of this art with the performing arts (theater, dance, singing) are very porous. This type of work focuses on gesture and no longer on the production of objects.

They take place in the ‘here and now’, in a specific location and context that more or less justifies the action. The latter can sometimes be repeated or improvised, violent or gentle, carried out using objects or not… These works can be received as provocative and make those who watch them feel discomfort.

The performance sometimes involves the audience. Performers as well as spectators share a sensitive and emotional experience.

The archives allow us to know these ephemeral works. They can be photos, videos, texts, protocols, drawings, testimonies …

If you want to go further, you can read this text on the specificities of performance archiving:

Archiving performance: uses, issues, and technical challenges

Uses

The archives bear witness to the event by transmitting information (realization, context, reception) that allows them to be traced and analyzed. These traces allow us to have knowledge of past events and thus to recount the history of the performance.

For researchers, curators or art historians, they are valuable resources because they allow to understand the way in which this practice developed. Thanks to them, we can trace the different artistic movements, their successions and therefore their trends and influences.

Specialists can compare different sources and validate the authenticity and processes of each work. Essential, especially when various interpretations jostle.

Technical issues and challenges

The creation of archives raises many issues regarding their manufacture, use and preservation. We must constantly question their status and pay attention to the different mediums that convey them. It should also be remembered that we submit them to our interpretation and therefore that we create the narrative.

Depending on the time and geographical context, the archiving methods are not the same and artists all have a different way of saving their works.Moreover, if it is possible from a photo to produce an archive, developing precise documentation requires rigor and meticulousness. It is difficult, if not impossible, to find a common method for archiving this type of work.

Indeed, the ephemeral and sometimes immaterial nature of art-action produces new challenges for institutions that wish to acquire and exhibit it. They must constantly renew and specify their conservation techniques (notably by means of forms) in order to respect the specificities of each work.

Debate over the use of photography and video

If we consider that these two mediums authenticate an action, we can also question this capacity and pay attention to the fact that they are fragmented and sources of interpretation.

That is to say, when the traces transmit information, this information is incomplete or even likely to be incorrect. Several observations can explain it: the first is that they transcribe a moment in a frame (2D) whereas the work was an action (3D).

The second is that each screenshot reflects a point of view (of the one who creates it). The third could be attributed to the technical limitations of cameras that are likely to transform space (framing, depth of field, modification of colors or brightness, distance between elements, lens size that distorts the subject…).

Conclusion

Safeguarding the existence of these works questions their transient and perishable nature. For some artists, this approach is not desirable. We can question our need to create an archive and the right to forget these works.

This shadow that surrounds them is also what allows them to stay alive since it invites us to speculate. It is also for this reason that the absence of archives does not detract from the fact that the work existed.

The archive is a construction, resulting from a collaboration between the artist, the one who captures it and the one who receives it, namely the spectator. It is an artistic choice and part of the continuity of the realization of the work, and that’s what we wanted to show by creating the website for all the artists of the School of Fine Arts in Paris.